VOLUME

ONE

IMAGES

NOTES

(1) Created by HUD in 2012, the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program introduced a conversion/private-financing concept for public housing. The program allows public housing agencies to move from Section 9 to a Section 8-based funding system, allowing them to access private financing to make repairs. The program has been extended three times and almost every state in the country has either completed a RAD project or has one in progress. In New York City, NYCHA plans to use RAD to convert 1/3 of their developments to Section 8. Currently, 17 RAD conversion projects have been completed, in-progress, or planned across 85 developments.

(2) To learn more about the fight to save Section 9, visit www.savesection9.org.

(3) Edward Goetz explores this trend at length in his 2011 article, “Where Have All the Towers Gone? The Dismantling of Public Housing in US Cities.” Goetz found that public housing removal has been more prevalent in cities facing gentrification pressures and in cities in which the management of public housing by local authorities has been subpar.

(4) In An Epilogue of Sorts (2007) Michelle Fine writes, “PAR (Participatory Action Research) assumes that those who have been most systematically excluded, oppressed, or denied carry specifically revealing wisdom about the history, structure, consequences, and fracture points in unjust social arrangements. PAR embodies a democratic commitment to break the monopoly of who holds knowledge and for whom social research should be undertaken.”

(5) Critical pedagogy situates education within struggles for social change and collective liberation. It’s explored in seminal works such as Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), Henry Giroux’s Theory and Resistance in Education: Toward a Pedagogy for the Opposition (1983), and Peter McLaren’s Life in Schools: An Introduction to Critical Pedagogy and the Foundations of Education (1994).

INTRODUCTION

“We must consistently challenge dehumanizing public representations of poverty and the poor. Restoring to our nation the understanding that people can be materially poor yet have abundant lives rich in engagement with nature, local culture, with spiritual values is essential to any progressive struggle.”— bell hooks, Belonging: A Culture of Place (2009)

“Beauty is not a luxury; rather it is a way of creating possibility in the space of enclosure. A radical art of subsistence, an embrace of our terribleness, a transfiguration of the given. It is a will to adorn, a proclivity for the baroque, and the love of too much.”

— Saidiyah Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019)

“In history, power begins at the source.”

— Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995)

New York City is home to the largest public housing authority in the United States with over 600,000 New Yorkers residing in NYCHA’s 325 public housing developments. Due to decades of disinvestment and mismanagement from all levels of government, there is an estimated capital needs deficit of $32 billion to make repairs to NYCHA’s crumbling infrastructure. Anyone who follows local news has likely seen the scandalous reports about the conditions this crisis in funding has created for residents, many of which break the habitability standards required of private landlords. As the City turns to the private sector to address the housing authority’s capital needs deficit through federal programs like RAD (Rental Assistance Demonstration),[1] a groundswell of housing justice organizers and residents are waging a powerful fight[2] to ensure that private equity and real estate interests get out of New York City public housing.

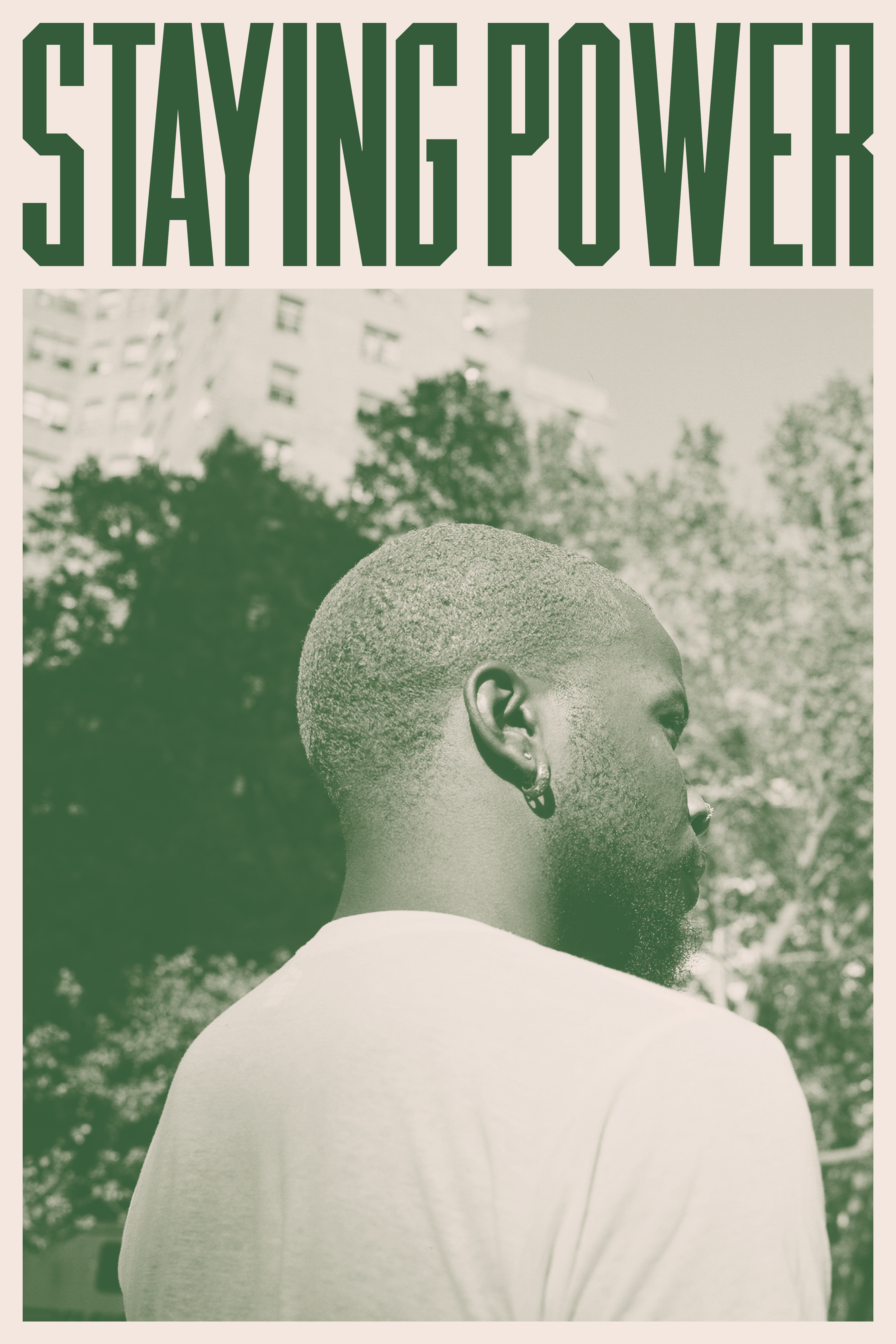

In many ways, public housing has become a national symbol of racialized urban decay. Residents are often scapegoated for the decline of the public housing program, which has already been set up to fail through decades of disinvestment. This narrative of failure has often been exploited by policymakers and real estate interests to justify the downsizing and dismantling of public housing programs in cities throughout the United States.[3] Staying Power explores how this dominant narrative can be challenged through visual and archival strategies. The project takes cues from the participatory action research[4] and critical pedagogy[5] traditions, affirming the rightful place of residents as experts and agents of community memory. The goal of the platform is to provide a publicly accessible curriculum about public housing history and highlight it as a stabilizing force in urban communities worth preserving and fighting for.

This first volume of Staying Power coalesces interviews, photographs, research, and artistic collaborations with public housing residents produced between 2019-2021. Content lives online and through limited edition risograph posters and booklets (also available to download as a free PDF here).